By Joe Boylan, Morgan AM&T

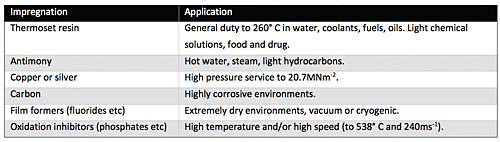

The inherent porosity of carbon-graphites can be filled with a variety of impregnants to enhance chemical, mechanical and tribological properties.

The terms carbon and graphite are often used interchangeably. This is unfortunate, as each form of the carbon element offers specific properties that can be used to benefit different types of applications.

Carbon-graphite seal face components and bearings are self lubricating, resistant to chemical corrosion, and capable of running at temperatures up to 538° C.

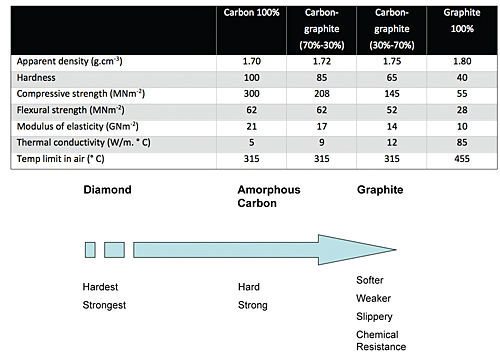

Amorphous, or free, carbon is a very hard, strong compound. The crystals exhibit a turbostratic disorder, which makes the material extremely resistant to wear. The strength and wear-resistant properties of this material make it of interest in some applications. However, these strengths can also be a weakness, as the carbon generates high friction when rubbed against other surfaces.

Graphite, on the other hand, is softer and relatively weak because of the crystalline order and closer spacing between the monoplanes and stacks. A graphite structure can be compared to a deck of cards, with individual layers able to easily slide off the deck. This phenomenon gives the material a self-lubricating ability, which is matched by no other material. External lubricants are simply not necessary.

Carbon and graphite together

It is possible to combine amorphous carbon and graphite to take full advantage of the strengths and weaknesses (see Table 1) of each of these two types of carbon. The proper mixture of the two materials is customized for specific sets of operating conditions and is strong, sufficiently abrasion resistant and has low friction. At the same time, these composites have excellent corrosion resistance and are capable of operating at temperatures in excess of 315° C for extended periods of time, depending on the specific composition. The ability to create materials that have these properties is the basis of the manufactured mechanical carbon materials that perform well in difficult tribological situations, such as pumps.

Processing carbon-graphites

Carbon-graphites are created by combining the two forms of carbon with coal tar pitch. The coal tar pitch acts as a temporary binder that holds the two structures together during the compression molding process (uniaxial or isostatic) in which near net shapes are formed. Following the molding operation, the parts are sintered at temperatures high enough to carbonize the coal tar pitch. The result is a structure that is completely carbon-bound, which contains the appropriate ratios of both carbon and graphite. This structure is extremely strong in compression and will not creep under load. The carbonization of the temporary binder leaves holes in the structure.

The formation of holes during the processing of a carbon-graphite composite has various advantages. The holes can be filled with resins, metals, carbon or inorganic salts (see Table 2), depending on the planned use of the material. These fillers serve to improve the strength, thermal conductivity and tribological characteristics of the material. Additionally, carbon-graphite can be sintered to an even higher temperature to convert the entire structure to graphite to provide especially good performance in high-temperature, high-speed applications.

Applications for carbon-graphites

Carbon-graphites vs. traditional lubricants — Carbon-graphites are used in a wide range of applications where traditional lubricating methods are not appropriate. For example, a typical oil-lubricated bearing struggles at temperatures below -40° C because of the high viscosity of the oil. Above 200° C, oils carbonize, making them abrasive and ineffective. Graphite bearings are capable of extended use at temperatures above 600° C. (See Figure 1)

Chemically aggressive environments — Chemically aggressive applications represent another application niche for carbon-graphite. For instance, sterilization processes tend to leach the oil from the structure of an oil-lubricated bearing. Also, solvents and radiation can break down lubricating oils, and low pressures can cause the oil to vaporize. Carbon-graphite materials are inherently stable and chemically resistant, making the material ideally suitable for these types of applications.

High-speed applications — The ongoing demand for efficiency is driving rotating equipment to ever-higher speeds and lower dynamic friction. Mechanical carbons provide stability for non-contacting designs and the needed lubricity on start-up and shut-down (when the components actually touch).

High-load applications — Lubricants are inappropriate in other applications for a variety of reasons. High loads can squeeze the lubricant from a surface. Without the hydrodynamic layer of lubricant, failure is imminent unless the material provides self lubrication. In some applications, such as those involving food handling, lubricants can contaminate the surrounding environment. Specific grades of carbon-graphites are approved for use in food handling applications.

Aerospace applications — Carbon-graphite and graphites are excellent materials for aircraft turbine engine main-shaft seals. The main shaft in a turbine engine rotates at very high speeds and operates in an environment of changing, high temperature conditions. Main-shaft bearing compartment seals are used to protect rotor support bearings from hot gases flowing through the engine and to prevent the loss of lubricant in the bearing compartments.

Design factors

Carbon-graphite bearings are used in both wet and dry operating conditions. Carbon-graphite allows engineers and designers to specify the bearing close to the boundary lubricated condition without the risk of seizure. Permissible loads and running speeds depend on the allowable wear rate. Shaft materials and surface finishes are important factors in the wear rates of carbon-graphite materials. As a rule of thumb, the harder and more polished the surface, the lower the wear. Aluminum and bronze should be avoided for use as shaft materials wherever possible.

Carbon-graphite materials are also widely used as rotating shaft and face seal materials (see Figure 2). They perform well when running against metal and ceramic counterfaces. Seals are manufactured from solid rings, split rings and segmented rings for use in both liquid and dry-running applications in the aerospace, nuclear, petrochemical and general marine industries.

Seal face materials require high strength and a relatively high modulus of elasticity to withstand deformation at the interface. Carbon-graphite seal materials provide the strength and rigidity that are especially important in high-pressure, zero-leakage mechanical end-face seals. High thermal conductivity is essential in removing heat from the interface.

Seal wear is a result of adhesive wear, chemical wear, erosive wear and sometimes radioactive wear. Carbon-graphite is inert to most chemical reagents so it survives where other materials fail. However, chemical wear is evidenced in certain strong oxidizing environments or where the additives are attacked by specific oxidizing reagents.

Impregnation of carbon seals can be done with a variety of materials to control permeability. In addition to thermoset resins, other types of impregnants include thermoplastics, metals and inorganic salts or glasses. The temperature limit of the impregnant places an upper limit on the operating temperature of the carbon parts.

Metals such as antimony, silver, copper, nickel, and babbitt can improve the strength, thermal conductivity and tribological characteristics of the materials. Impregnants made of inorganic salts (usually phosphate or borate) and glasses are used in high temperature applications. Carbons impregnated with soluble salts must be handled carefully to avoid exudation, especially under humid conditions, although the loss of the impregnant rarely affects any physical property of a seal other than permeability.

Blistering is a critical concern with carbon seal materials. Strangely, the reason blistering occasionally occurs is not clear. One of the most popular explanations is that a certain amount of fluid becomes absorbed in the carbon substrate and expands due to frictional heat, creating a subsurface pressure and an eventual crater in the seal face. Another theory is that softer mating materials can tend to tear pieces from the carbon-graphite in the presence of heavy hydrocarbons. Blistering is most often found in applications involving hydrocarbons or cyclical temperature service, such as air conditioning compressors. In some cases, the use of silicon carbide as a mating surface will reduce or even eliminate a blistering problem, possibly because of its high thermal conductivity and hardness

Materials selection and suitability

Loads, speeds, temperatures, mating materials, cost constraints and projected volume are critical factors to be kept in mind when selecting materials. Scores of base carbon materials are available with hundreds of modifications that can be customized for specific designs and environments. General service carbon-graphites are usable up to 260° C while special grades are available that provide resistance up to 538° C. Special carbons and impregnants are used for seal applications in the 260° to 538° C temperature range.

These materials are chemically inert, temperature resistant, lightweight, resilient, dimensionally stable and impermeable to gases and liquids. They can be molded to size or machined to close tolerances, impregnated, plated, vulcanized to rubber and cemented or shrunk into housings or retainers—a truly versatile set of advanced materials.

Morgan AM&T

www.morganamt.com

Tell Us What You Think!