Written by Randy Lammers, Technical Instructor | Co-host YouTube series, Würth Knowing

Würth Industry North America

The head of a 5/8″ diameter, zinc-plated socket cap screw bursts off a piece of recently produced equipment and shoots, much like a bullet, across a manufacturing plant, through a metal toolbox — just missing a nearby worker. A 5/16″ wave washer fractures, causing a product recall of $400,000. A hardened wood screw breaks, causing a chair to collapse and resulting in the loss of life.

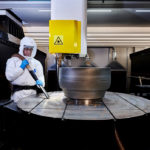

This is what hydrogen embrittlement looks like on a bolt.

There are several high-cost examples of product failures, leading to equipment malfunction, personal injury, or worse because of fastener fractures. These can result from hydrogen-assisted cracking, more commonly known as hydrogen embrittlement (HE).

This is a complex scientific subject with much research and many papers written to explain the phenomenon, as well as ongoing testing and investigation. Despite years of accumulated insight, there are still risky choices made concerning HE in the fastener industry.

Hydrogen assisted cracking in fastener applications

Atomic hydrogen is one of the smallest-known elements and is all around us. The potential damage, at a micro-level, in hardened steel fasteners that have been electroplated is of particular concern. Hydrogen atoms are introduced to the steel in high concentrations during the pre-cleaning and electrolytic process of applying metallic materials (commonly, zinc).

After electroplating, a layer of chromate/passivate is added to provide additional corrosion protection and good aesthetic values. This high concentration of introduced hydrogen provides an opportunity for these atoms to accumulate and become trapped within the steel’s molecular structure. Depending on the metallic plating’s permeability, the plated surface finish acts like a barrier to hydrogen effusion.

Externally applied load and/or internal residual tensile stress leads to a widening of the steel’s grain boundaries. And hydrogen atoms are highly mobile. Now consider such widened grain boundaries where free hydrogen atoms accumulate to such a degree that pressure is created within the boundary. This accumulation of pressure can cause the grain boundary to crack open in susceptible hardened steel.

Eventually, the molecular structure of the steel is compromised and can no longer withstand the applied stress. The structure fails from internally cracked grain boundaries and a sudden burst of the total structure occurs. Granted, this fracturing process takes time. Typically, a delayed failure occurs one to 48 hours after fastener installation, once sufficient stress has been applied.

What is susceptible hardened steel?

Consider which is stronger, a candy cane or a piece of soft chewy taffy? Certainly, a candy cane is hard and has high tensile strength, but it’s also brittle. Taffy is soft, easily stretches in tensile pull, and is ductile. Now, think about creating pressure within the structure of a candy cane. What would happen? It would likely explode or burst, which is how a hydrogen embrittlement fracture is described — as a burst.

What’s more: the surface of a hydrogen embrittlement rupture looks similar to rock candy. So, the hardness of a candy cane is highly susceptible to failure because of HE cracking.

What would happen if you applied the same pressure within the structure of a piece of taffy? It would likely stretch and relax, thanks to its soft ductile capabilities. The hardness of taffy would be considered non-susceptible.

This provides a simplified analogy of the correlation between steel hardness and susceptibility to an HE fracture.

A close-up of hydrogen embrittlement at work.

For susceptible material hardness, reference ASTM F1941 and ISO 4042 specifications for electroplating fasteners. ASTM F1941 places the threshold above 39 HRC and ISO 4042 above 390 HV.

When electroplating fasteners with material hardness in the susceptible category, specifications mandate the parts are baked after electroplating and before the addition of chromate/passivate and/or any topcoat materials.

Baking facilitates the outgassing of the permeated hydrogen atoms. Temperatures of 375-425o F (190-220o C) are applied for eight to 24 hours, depending on the fastener type, size, and strength, in combination with the plating system and process.

In recent studies, the practice of baking susceptible materials for four hours has proved inadequate for most fasteners.

To further avoid HE, some industry and company standards have placed the susceptible material hardness threshold at 32-34 HRC (~320 HV) as a precaution against manufacturing errors in raw material, fastener production, and electroplating process. SAE J429 Grade 8 and ISO 898 Property Class 10.9 have material hardness above this threshold and would fall into this susceptible category.

Unfortunately, these errors are common when buying from a supply chain with unknown sources and controls within the supply chain. It’s advisable to consider materials in this lower hardness range as susceptible, which should be baked when electroplated.

Now, what is the risk of electroplating fasteners with material hardness above 39 HRC (390 HV)? The introduction of ASTM F1941 states in part:

With normal methods of depositing metallic coatings from aqueous solutions, there is a risk of delayed failure due to hydrogen embrittlement for case hardened fasteners and fasteners having a hardness above 39 HRC. Although this risk can be managed by selecting raw materials suitable for the application of electrodeposited coatings and by using modern methods of surface treatment and post heat-treatment (baking), the risk of hydrogen embrittlement cannot be completely eliminated. Therefore, the application of a metallic coating by electrodeposition is not recommended for such fasteners.

Consequently, it’s advisable to avoid using any fastener with a hardness above 39 HRC (390 HV) that has been electroplated.

High-risk items:

- Inch series socket cap screws, including button head and flat head

- Metric property class 12.9 fasteners

- Any spring action washer including wave, conical, Belleville, and helical-lock washers

- Any spring steel clips

- Retaining rings

- Spring pins

- Any part above 39 HRC (390 HV) that will or might experience tensile stress

What can you do?

Use low to non-hydrogen generating finishes, such as mechanically applied zinc, thermal diffusion zinc, or zinc-flake coatings. If the high strength of an inch series socket cap screw is not required for the application, use readily available metric property class 8.8 or stainless steel. There are less risky solutions to every potential HE part, research to ensure the ideal choice.

In conclusion, HE is a delayed failure not seen during assembly. It’s advisable to bake parts between 34 to 39 HRC (320 – 390 HV) when purchasing through an unknown or uncontrolled supply chain. Avoid electroplating fasteners with a hardness above 39 HRC (390 HV).

Hydrogen embrittlement is a complex scientific subject. Further investigation and studies are ongoing. Stay informed as more information on this phenomenon is released. This is a serious topic and failure is paired with a high cost. The risk is not worth the reward.

Its a nice explanation, i am Adithya Reddy a master’s student in TU Freiberg in Germany doing my masters Thesis on Hydrogen embrittlement of high strength steels. As a Metallurgy engineer we have to find a way to eliminate the hydrogen embrittlement and way to find to transport the hydrogen for energy source applications.